|

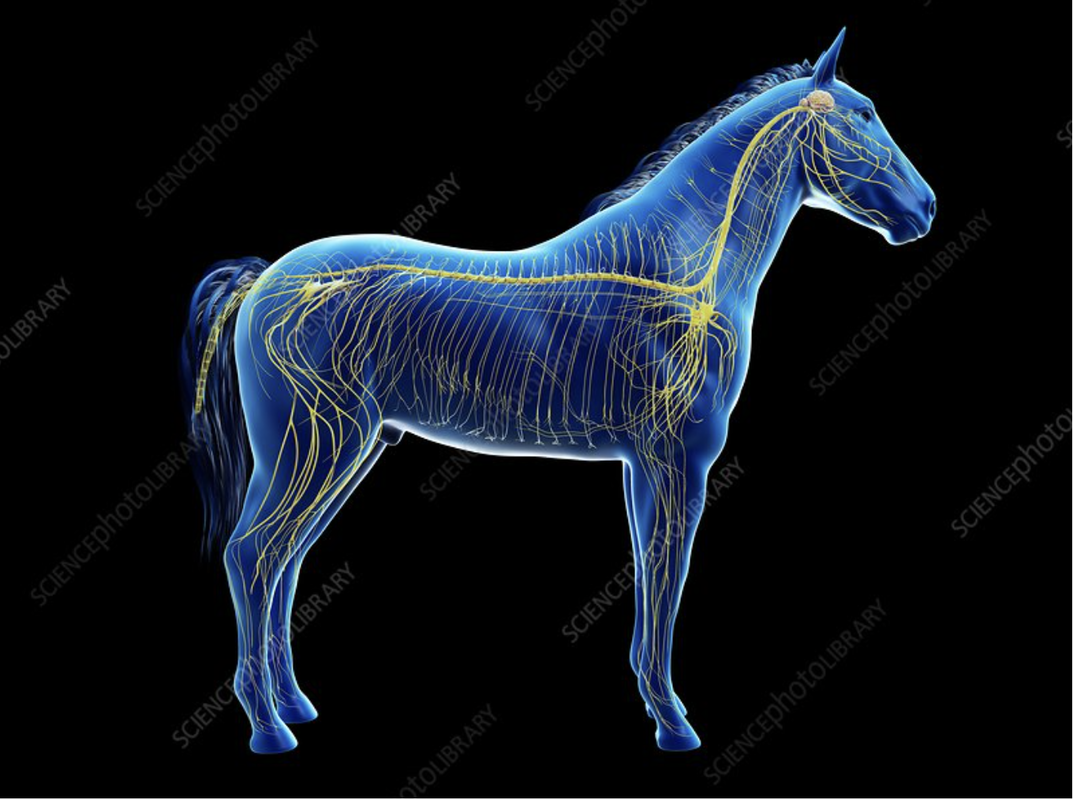

From an anatomical perspective the nervous system is made up of the Central Nervous System (CNS) (brain and spinal cord), and Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) (cranial and peripheral nerves). From a functional perspective it is divided into the Somatic Nervous System (voluntary movement), and the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), which controls involuntary (visceral) functions demanded for maintaining the overall physiological balance of bodily functions. In clearer terms the ANS is responsible for the involuntary bodily functions of the cardiovascular system, respiratory system, digestive system, urinary system, reproductive functions and mobilization in the body’s resources under stress. However, to achieve this it must be in balance. Any trauma, accident, drugs, chemicals, physical or mental abuse, including a horse being put under too much pressure, or an underlying genetic predisposition, which makes these types more susceptible, may cause the ANS to be out of balance. The ANS of the horse is controlled by two branches: 1) Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) – fight or flight. 2) Parasympathetic nervous system – rest and digest. The parasympathetic system is in constant opposition to the sympathetic system. The sympathetic side there is the fight/flight/let me out of here response, and on the other, the parasympathetic there is rest, relax, eat, and digest. Real or imagined circumstances can quickly trigger the nervous response in horses (and humans). When the sympathetic side of the ANS is dominant the horse cannot help its inappropriate response to everything or anything. At the highest end of this scale you see a horse in a blind panic, eyes boggling, escaping or trying to, even at the expense of hurting itself and others, sweating profusely, heart rate and respiration through the roof. Horses may experience an activated SNS from several different sources: Transportation: In natural settings, horses spend up to two-thirds of their time moving. Standing for long periods in a vehicle can disrupt a horse’s normal routine. Exertion rhabdomyolysis (ER): Under normal conditions, a horse’s heart and respiratory rate will slow after exercise. If cramping and muscle pain occur during this period, it can activate the SNS. Oxidative stress: Normally, almost all the oxygen your horse consumes turns to water and carbon dioxide. A remaining 1-2% of unused oxygen forms reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can degrade proteins. Cold stress: For each degree the ambient temperature falls below a horse’s critical temperature, the animal expends about 1% more energy. Heat stress: When a horse exercises it can produce up to 50% more body heat, increasing sweat output and respiration rate. Ulcer stress: In both an eating and resting state, a horse’s stomach produces acid. For this reason, ulcers can be common. Horses that suffer from an Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) imbalance are typically regarded as being nervous, highly strung, inconsistent, or fidgety. Often the best of trainers have problems with horses with ANS imbalance. They may feel like at last they’ve found the key to a particular horse then suddenly, for no apparent reason, the horse falls to pieces again and can’t concentrate on the job at hand. Some people think the horse is just being naughty, resistant to training or having behavioral problems instead of realizing there may be a fundamental physical problem.

Remember when there is an imbalance of the ANS, the horse can not help his/her response; it is involuntary. Maintaining a balance between the SNS and PNS when triggers are present can promote healthy weight, metabolism and overall function in your horse. Taking a proactive approach for nervous system wellness is an important element in maintaining overall health: Look for natural body language: In a resting state, a horse’s ears are turned out to the side and its head is lowered. A relaxed horse may also show a drooping lip, slack mouth or chewing when not eating. These behaviors indicate your horse’s PNS system is functioning and promoting calmness. Establish a routine: A basic routine will go a long way in providing stability. A horse conditioned to expect feeding and exercise at certain times of day will spend more time in “rest and digest” mode. Allow for locomotion: Before they were domesticated, horses evolved to be grazing animals. As a result, locomotion supports healthy digestion, respiration, metabolism and physical health. Giving your horse time and space to move while grazing can help satisfy this need. Promote socialization: Horses have a natural instinct for social interaction over isolation. Providing socialization opportunities for your horse to be around other horses can promote overall wellness and behavioral health. Pace changes appropriately: At some point, you will have to make changes to your horse’s routine. Carefully planning and pacing these changes helps maintain your horse’s expectations and overall behavioral health. Provide proper nutrition: Ensure your horse gets the appropriate amount of carbs, protein, fats, vitamins and minerals to ensure healthy nutrition. In many cases, a horse with a thoughtful routine and healthy diet will exhibit calmer behavior and react less drastically to anxiety triggers. Maintaining a regular bodywork session: Bodywork is a “body hack” via the vagus nerve and parasympathetic nervous system. It is pressing the reset button by allowing the nervous system to release unwanted muscles tension which is being held throughout the body, it boosts digestion and allows the body to “recover” from the stresses of modern day life. Staying on regular bodywork schedule allows your horse to access his parasympathetic nervous system by allowing his body to get back to the "business of living" and helping all his/her systems to function properly.

0 Comments

|

AuthorMeghan Brady is a equine industry professional specializing in a holistic approach for both horse and rider to enhance performance and well being. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed